The Quebec Privacy Regulator’s Guide on Law 25-compliant Privacy Impact Assessments

This article is part of our Law 25 Blog Series, which provides readers with a 360° view on Law 25 (formerly known as Bill 64) and its sweeping amendments to Quebec’s Act respecting the protection of personal information in the private sector (“ARPPIPS”).

On September 22, 2023, Quebec’s privacy regulator, the Commission d’accès à l’information du Québec (“CAI”), released its long-awaited guide (available in French only) on conducting privacy impact assessments (“PIAs”) as required by Law 25. The guide provides a roadmap for conducting PIAs and establishes a methodology for quantifying and addressing privacy risks. Alongside the guide, the CAI published a PIA template (available in French only), which serves as a model that can be used by organizations to complete Law 25 compliant PIAs. The CAI states that using the PIA template is not mandatory and recommends adapting it to the context and scope of the assessment at hand.

While the CAI’s guide addresses PIA requirements that are relevant for both private and public sector organizations, this article focuses on the legal obligations that apply to the private sector.

What is a PIA?

PIAs are evaluations that organizations undertake to assess and identify the potential risks to individuals’ privacy that may result from projects involving the collection, use, or communication of their personal information and to propose measures to adequately mitigate such risks. PIAs also help organizations to ensure that their projects are more likely to continuously comply with applicable privacy laws and underlying principles.

When Should a PIA be Conducted?

Law 25 requires organizations to conduct a PIA before engaging in projects that involve any of the following three categories of activities.

- Communicating personal information to a third party wishing to use the information for study or research purposes or for the production of statistics without the consent of the persons concerned.[1]

In such cases, personal information can only be communicated if the organization meets the following five factors, which must be assessed in the PIA.

i) The organization must demonstrate that the objective of the research can only be achieved if the information is communicated in a form allowing the persons concerned to be identified. Otherwise, only anonymized or de-identified information should be used.

ii) The organization must conclude that it is unreasonable to require the consent of all persons concerned.

iii) The organization must conclude that the objective of the study or research or of the production of statistics outweighs, with regard to the public interest, the impact of communicating and using the information on the privacy of the persons concerned. This assessment should take into account societal benefits, the sensitivity of the personal information being communicated, and the potential privacy risks.

iv) The organization must make sure that personal information is used in a manner that ensures its confidentiality. This confidentiality requirement extends beyond the communication of personal information; it must be maintained throughout all phases of the project.

v) The organization must ensure that only the necessary information is communicated. Particular attention should be given to information that can allow an individual to be identified directly or indirectly (such as addresses, full postal codes, health insurance numbers, date of birth, or age) and sensitive information.

Furthermore, such communication must be the subject of a written agreement between the organization and the researcher.[2] This agreement must be provided to the CAI and comes into force thirty days after receipt by the CAI. No communication of personal information may occur during the thirty days. While the agreement does not have to be approved by the CAI, the CAI may at its discretion contact the parties and suspend the agreement or exercise other oversight powers conferred by the ARPPIPS.[3]

- Implementing any project to acquire, develop, or overhaul an information system or electronic service delivery system which involves the collection, use, communication, keeping, or destruction of personal information.[4]

“Information systems” can take multiple forms, for instance:

- A computerized file processing system;

- A videoconferencing or collaboration software;

- A biometric system;

- An artificial intelligence system;

- A smart card or RFID system;

- A video surveillance system;

- A statistical system; and

- A payroll system.

It should be noted that information systems do not necessarily have to be computerized.

“Electronic service delivery systems” can also take multiple forms, for instance:

- A self-service kiosk;

- An RFID/NFC payment service;

- A member area of a website;

- An electronic record; and

- A mobile application.

- Communicating personal information outside Quebec or entrusting a person or body outside Quebec with the task of collecting, using, communicating, or keeping personal information.[5]

In such cases, the PIA should take into account the following factors:

i) The sensitivity of the personal information;

ii) The purposes for which the personal information is to be used;

iii) The protection measures, including those that are contractual, that would apply to the personal information; and

iv) The legal framework and personal information protection principles applicable in the jurisdiction in which the information would be communicated.

The personal information can only be communicated if the PIA determines that the information would receive adequate protection in light of applicable legislation and “generally recognized principles regarding the protection of personal information.”[6] Furthermore, any communication of personal information outside Quebec must be the subject of a written agreement that takes into account the PIA’s results and, if needed, agreed-upon terms to mitigate identified privacy risks.

Under Law 25, there is no retroactive obligation to conduct a PIA for projects completed before the applicable date of entry into force (i.e. September 22, 2022 for categories 1 and 2 above and September 22, 2023 for category 3).[7] However, a PIA will be required if a project was altered or entails communication of personal information outside Quebec after such date.[8] Moreover, PIAs should be carried out by the organization that holds the personal information. The responsibility for conducting a PIA cannot be delegated to subcontractors, suppliers, or partners, although their input can be valuable to the assessment.[9]

How to Conduct a PIA?

The CAI’s guide sets out multiple steps and sub-steps that organizations are encouraged to follow when preparing and conducting PIAs. We have condensed and summarized these below.

- Define the Project and its Objectives

First, the CAI’s guide recommends documenting contextual information relating to the project that will facilitate the assessment and mitigation of privacy risks. Organizations should describe the nature and scope of the project, its context, as well as its implementation timeline, and other relevant factors.

Organizations should also define the project’s objectives. These objectives must be related to serious and legitimate reasons.[10] The following examples of objectives are listed in the guide:

- Introducing a new public service;

- Taking an existing service online;

- Increasing the security of a facility;

- Combatting fraud;

- Enhancing the detection of rare health issues;

- Ensuring regulatory compliance;

- Sustaining competitiveness; and

- Improving customer experience by developing an upgraded platform.[11]

This in turn allows organizations to evaluate a project’s “proportionality” as regards the proposed collection and use of personal information, which must be ensured throughout the implementation of the project. According to the CAI guide, proportionality is achieved if:

- There is a rational link between the project and its objectives (i.e., the project is an effective way of achieving the objectives);

- The impact on privacy is minimal or there are no other effective and less intrusive solutions; and

- The tangible benefits outweigh the consequences or harm on the persons concerned.[12]

- Delineate the PIA Scope and Responsibilities

Second, organizations should establish a well-defined scope for the PIA and identify the roles and responsibilities of the relevant stakeholders involved in its completion. In order to properly determine the PIA’s scope, organizations should take into account factors such as the project’s scale, objectives, and duration as well as “the sensitivity of the information concerned, the purposes for which it is to be used, the quantity and distribution of the information and the medium on which it is stored.”[13] This will then inform:

- The number of stakeholders to involve;

- The amount of time required;

- The level of detail of the PIA report;

- The supporting documentation to be developed; and

- The quantity and level of detail of the measures taken to mitigate privacy risks.[14]

Law 25 requires an organization to consult the “person in charge of the protection of personal information” (e.g., chief privacy officer) when conducting a PIA.[15] The CAI’s guide also lists examples of other categories of internal and external stakeholders who, depending on the scope of the PIA, might be relevant to the assessment. Such stakeholders may include, for instance, representatives from an organization’s legal, HR, and client-relations departments as well as subcontractors, partners, and clients.[16]

- Make an inventory of personal information

Third, when conducting a PIA, organizations should make an inventory of personal information involved in the project. The inventory should allow organizations to have a complete picture of the nature, sensitivity, quantity, intended use, and lifecycle of the personal information. The inventory also helps ensure that the organization will only process personal information that is necessary for carrying out the project’s serious and legitimate objectives. The CAI proposes a list of questions to guide an organization’s reflection when making such an inventory, which we have translated and summarized below.[17] We note that these questions will not only be relevant for completing the inventory, but also when completing other parts of the PIA.

What? | ✓ What types of personal information will be collected, communicated, used, or kept in the context of this project? ✓ What is the nature of this information (e.g., is it sensitive)? |

Why? | ✓ Why does the organization want to collect, use, disclose, or keep personal information? ✓ What is the purpose of using this information in the project? ✓ How is access to this information necessary for the functions of those who will have access to it? |

How much? | ✓ How much personal information will be involved in the project? ✓ How many persons will be affected by the project? ✓ What is the projected duration of the project? ✓ What is the projected geographical scope of the project? |

Who? | ✓ What categories of persons will have access to this information within the organization or externally? |

How? | ✓ How or by what means will personal information be collected, used, communicated, or kept within (or outside of) the organization? ✓ How will the organization destroy this information once the purpose justifying its collection (or communication or use) is achieved? ✓ What method of destruction (or anonymization) will be used? |

Where? | ✓ Where will this information be distributed and kept within (or outside) the organization? ✓ On what type(s) of media and under what conditions will it be kept? |

When? | ✓ When will the information be destroyed or anonymized? |

- Make a List of Obligations

Fourth, organizations should identify their applicable privacy obligations, which primarily stem from laws and regulations, but also internal policies and international norms.[18] Such privacy obligations include compliance with factors that we have listed at the outset of this article, which (as noted) may vary depending on which of the three listed scenarios give rise to the statutory obligation to conduct the PIA.

In Canada, both the federal government and certain provinces have their unique privacy laws and regulations. Therefore, organizations operating in multiple provinces must consider the specific obligations imposed by the relevant legal framework in each relevant jurisdiction. Furthermore, organizations with a global presence must consider the laws of other countries, which may impose significantly different obligations compared to those in Canada. Organizations should be particularly attentive to laws with extraterritorial reach, such as the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation.

- Assess Privacy Factors

Lastly, organizations should conduct an assessment of all of the factors that will have a positive or negative effect on privacy.[19] This step is the essence of the PIA and is meant to leverage information gathered by completing the preceding steps. The CAI’s guide identifies three main factors for the assessment, which we have summarized below.

i) Applicable Legislation

To respect the first privacy factor, organizations must ensure that the project complies with applicable privacy legislation and underlying principles. Compliance must be upheld with respect to all categories of personal information involved in the project and throughout their lifecycle, failing which necessary adjustments must be made to the project. The CAI encourages organizations to seek legal advice particularly for this factor in the event of uncertainty.

ii) Privacy Risks, Causes, and Consequences

To respect the second privacy factor, organizations should identify privacy risks and their causes as well as describe and evaluate their potential consequences.[20] To do so, the CAI guide indicates that organizations should consider events or situations that could arise from the project’s implementation and which would jeopardize the privacy of the persons concerned. The following are examples of privacy risks, causes, and consequences listed in the guide – which can serve as inspiration when evaluating this second factor.[21]

Risks

- Excessive collection of information;

- Unjustified or unnecessary creation of information;

- Inadequate disclosures at points of collection of information;

- Unauthorized disclosure of information;

- Decision-making based on inaccurate or equivocal information;

- Personal information theft;

- Intrusion on privacy which is disproportionate to the project’s purpose;

- Retention of information beyond its period of utility; and

- Re-identification of anonymized personal information.

Causes

- Deficient processes;

- Errors in handling information;

- Lack of knowledge or training;

- Insufficient or non-existent monitoring mechanisms;

- Inadequate attribution of responsibilities;

- Malicious behaviour;

- Excessive collection of information;

- Defective or outdated technology;

- Non-justified or unnecessary use of sensitive information;

- Absence of consent;

- Insufficient mechanisms for ensuring the accuracy of personal information; and

- Existence of an alternative which is less intrusive and sufficiently efficient for attaining the project’s objective.

Consequences

- Identity theft and fraud;

- Danger to individuals’ safety and well-being (e.g., potential harassment);

- Financial loss and missed opportunities;

- Damage to reputation;

- Unwanted solicitations; and

- Intrusions and other disruptions on individuals’ privacy.

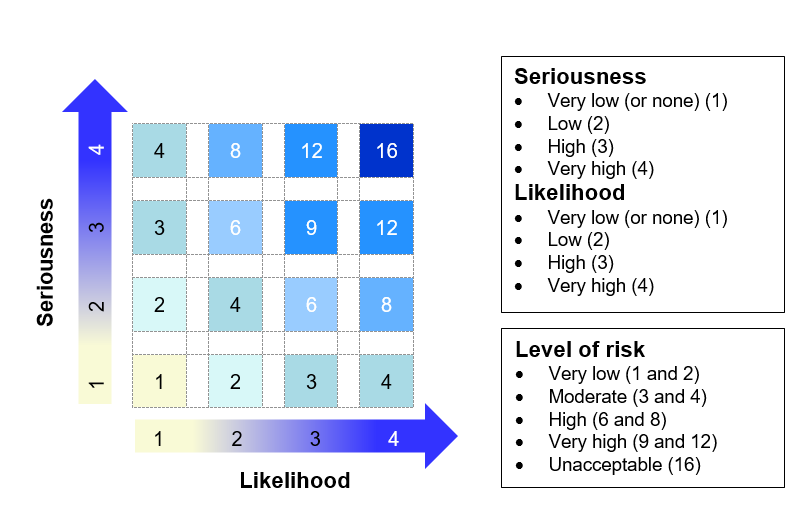

Once the potential risks, causes, and consequences are identified, the organization should qualify the level of risk and present the results of the analysis. The CAI acknowledges that this is a subjective exercise and that there is no prescribed method that must be followed. Nevertheless, the CAI provides an example of a method where risk is quantified based on the potential seriousness of the privacy risks and their likelihood of occurrence. In practice, this can take the form of a rating system, such as the one from the CAI’s guide which we have reproduced and translated below.[22]

iii) Strategies to Avoid or Effectively Reduce Privacy Risks

To respect the third privacy factor, organizations should put in place strategies to effectively avoid or reduce the project’s privacy risks. Strategies can seek to reduce the seriousness or the likelihood of such risks. The following examples of strategies are listed in the guide:

- Planning a periodic review of the various collections of personal information;

- Implementing a document management system that enables automated application of a retention schedule;

- Reviewing computer access allocation and management processes;

- Periodically reviewing security parameters for electronic service delivery;

- Reviewing confidentiality clauses in contracts;

- Establishing and scheduling a training and awareness program for employees;

- Conducting an information campaign about the new use of personal information;

- Logging access and monitoring logs to detect anomalies;

- De-identifying or anonymizing information if its use in a directly identifiable form is not required.[23]

Finally, once a PIA is completed, organizations must ensure that risk mitigation measures that were identified in the PIA are effectively applied to the project. Furthermore, organizations must update the PIA if changes that could have an impact on privacy are subsequently brought to the project. Organizations should also keep their PIA current with evolving industry standards and new legal obligations, such as requirements of data portability under Law 25 which will come into effect on September 22, 2024.[24] In short, the preparation of a PIA is an iterative process, the results of which may evolve over time.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the CAI’s guide provides a structured methodology for conducting PIAs and provides organizations with helpful tools that can be tailored to fit specific projects that require PIAs. While use of such resources is not mandatory, they paint a picture of what the CAI is likely to consider compliant with Law 25. To protect individuals’ privacy and avoid potentially costly regulatory fines and investigations, organizations should take a proactive stance to PIAs and integrate their completion into their internal compliance processes.

Stay tuned for further McCarthy Tétrault’s publications on this subject. To learn more about how our Cyber/Data Group can help you navigate the privacy and data landscape, please contact national co-leaders Charles Morgan and Daniel Glover.

[1] ARPPIPS, RLRQ c P-39.1, s. 21.

[2] Ibid at s. 21.0.2.

[3] See Quebec, Commission d’accès à l’information du Québec, Communication de renseignements personnels sans consentement à des fins de recherche - La conclusion et la transmission de l’entente (Quebec : CAIQ, 2023) at <https://www.cai.gouv.qc.ca/communication-renseignements-personnels-sans-consentement-fins-recherche/entente/>.

[4]Supra note 1 at s. 3.3.

[5] Ibid at s. 17.

[6] See Quebec, Commission d’accès à l’information du Québec, Guide d’accompagnement – Réaliser une évaluation des facteurs relatifs à la vie privée (Quebec : CAIQ, 2023) at 38, n 19. The CAI cites the OECD’s Recommendation of the Council concerning Guidelines Governing the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data, the Fair Information Practice Principles (FIPPs) of the Federal Trade Commission, Canada’s Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act, and the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation as sources which contain “generally recognized principles regarding the protection of personal information”.

[7] Ibid at 6.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid at 10.

[10] Ibid at 8-9.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid at 9.

[13] Supra note 1 at s. 3.3(4).

[14] Supra note 6 at 14-15.

[15] Supra note 1 at s. 3.3 (2).

[16] Supra note 6 at 10-11.

[17] Ibid at 45.

[18] Ibid at 17-18.

[19] Ibid at 19.

[20] “A privacy risk is a situation or event that may or may not occur in the future and that would cause loss or harm to a person’s privacy or personal life” [translated by the authors]. See Ibid at 20.

[21] Ibid at 20-22.

[22] Ibid at 23.

[23] Ibid at 25-26.

[24] See Law 25 amendments to s. 27 of the Act respecting the protection of personal information in the private sector, RLRQ c P-39.1.