Deans Knight: The Supreme Court of Canada Applies the General Anti-Avoidance Rule to Supplement a Well-Established Specific Anti-Avoidance Provision

Overview

On Friday, May 26th, 2023, the Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”) released its much anticipated decision in Deans Knight Income Corporation v. His Majesty the King.[1] A 7-1 majority applied the general anti-avoidance rule (“GAAR”) in section 245 of the Income Tax Act (Canada) (“Act”) and concluded that Deans Knight Income Corporation’s (the “Taxpayer”) use of tax attributes to shelter income from a new business abused subsection 111(5), even though it did not undergo a change in de jure control.

The decision has several important implications for taxpayers and is liable to create further uncertainty as to when the GAAR might apply:

- First, the majority held that the GAAR is not limited to unforeseen tax strategies. Even where Parliament knew about a specific tax strategy (i.e., loss trading), implemented a specific anti-avoidance rule to prevent that strategy (i.e., 111(5)), and the taxpayer complied with the text of that rule, the GAAR can still apply.

- Second, taxpayers should beware of relying too much on the text of the statute in a GAAR case, even when it is clear. The text is only the means by which Parliament sought to achieve the objective of a particular provision, but it is not exhaustive of that objective. Extrinsic aids, including legislative history, play a significant role in determining the object, spirit, and purpose of the provisions at issue.

Background

The Taxpayer was a public corporation with unused non-capital losses and other deductions (“Tax Attributes”). In 2008, facing financial difficulties, the Taxpayer entered into an agreement (“Investment Agreement”) with an arm's length company, Matco Capital Ltd. (“Matco”), to monetize its Tax Attributes.

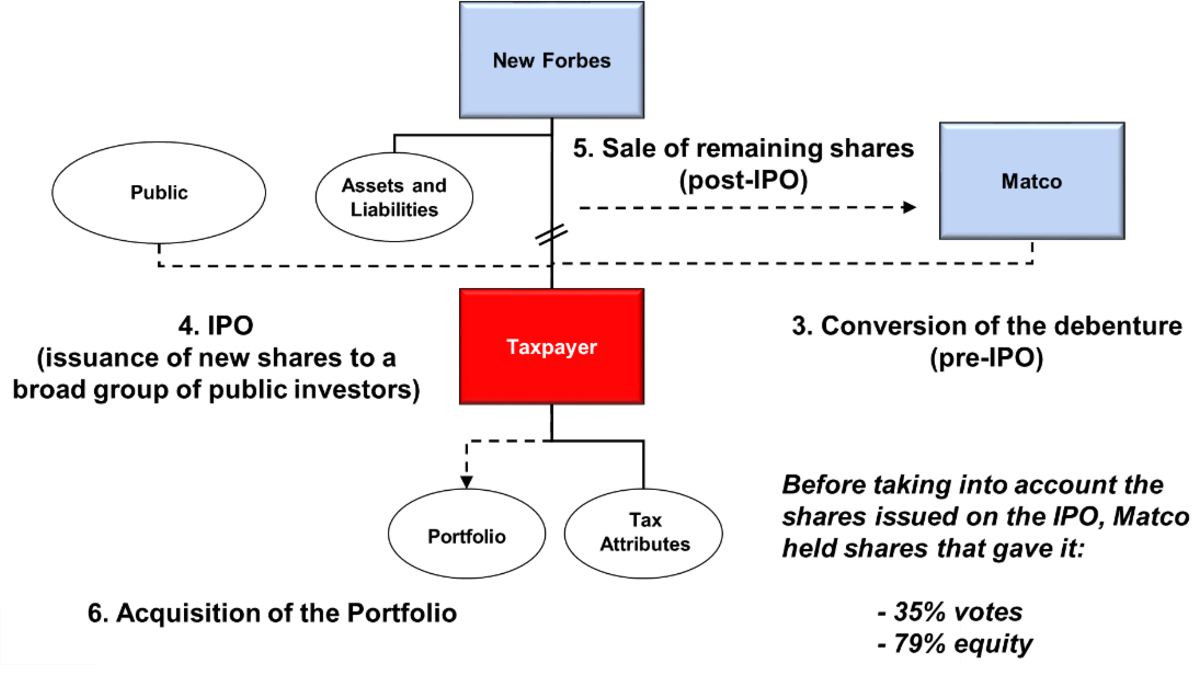

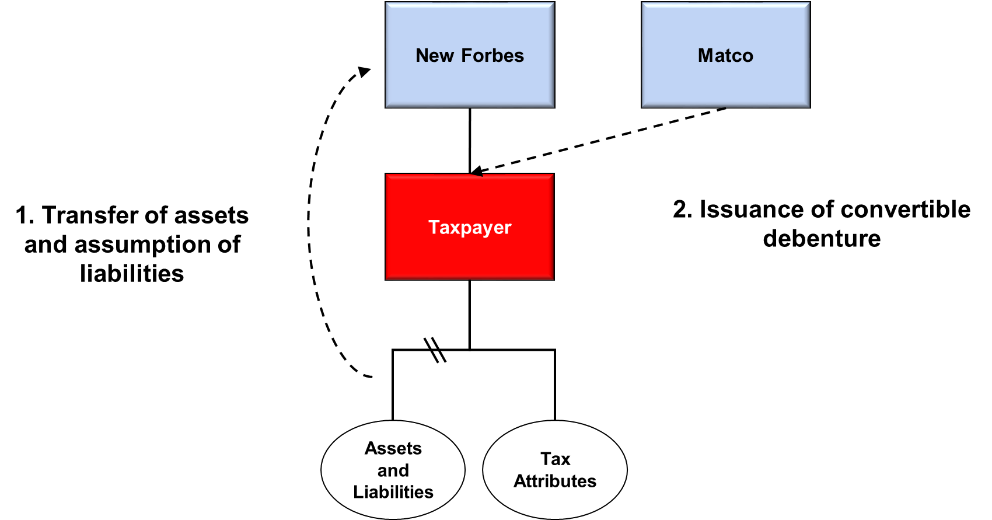

Pursuant to the Investment Agreement, the Taxpayer transferred its assets to a newly incorporated parent company (“New Forbes”), and New Forbes also assumed the Taxpayer’s liabilities. Matco then purchased a convertible debenture issued by the Taxpayer for $3 million that could be converted into a minority percentage (35%) of the voting shares of the Taxpayer and non-voting shares, which together represented 79% of the equity in the Taxpayer. Matco began a search for an income-generating business opportunity that could allow the Taxpayer to make use of the Tax Attributes to offset income from a new line of business (a “Corporate Opportunity”).

The arrangement was structured so that neither Matco nor anyone else could acquire de jure control of the Taxpayer, since an acquisition of de jure control would trigger the application of subsection 111(5) and prevent the use of the Tax Attributes to offset income from a new line of business. While the Investment Agreement was carefully drafted and did not trigger an acquisition of de jure control, it did provide that, while Matco was searching for a Corporate Opportunity, the Taxpayer was prohibited from undertaking several actions including issuing or selling shares of the Taxpayer or taking any action causing a change of control without the prior consent of Matco.

Matco arranged for the initial public offering (the “IPO”) of the Taxpayer, the proceeds of which were used to acquire a portfolio of high-yield bonds (the “Portfolio”). Matco converted its debenture into shares of the Taxpayer and, immediately after the IPO, New Forbes sold the remaining shares of the Taxpayer to Matco for $800,000.[2] The Taxpayer deducted the Tax Attributes against the income earned from the Portfolio in its 2009 to 2012 taxation years.

Lower Court Decisions[3]

The Tax Court of Canada (“Tax Court”) held that the GAAR did not apply. The Tax Court found that the object, spirit and purpose of subsection 111(5) of the Income Tax Act (Canada) (“Act”) is to “target the manipulation of losses of a corporation by a new person or group of persons, through effective control over the corporation’s actions”.[4] Since Matco did not have “effective control” over the Taxpayer, the transactions did not frustrate or defeat the object, spirit, or purpose of subsection 111(5).

The Federal Court of Appeal (“FCA”) allowed the appeal. The FCA rearticulated the object, spirit and purpose of subsection 111(5) as being “to restrict the use of specified losses, including non-capital losses, if a person or group of persons has acquired actual control over the corporation’s actions, whether by way of de jure control or otherwise.”[5] In so doing, the FCA created a new “actual control” test, different from the standards of de jure and de facto control that are expressly set out in the Act and which have governed previous tax cases. Ultimately, the FCA applied this newly created standard and found that the terms of the Investment Agreement gave Matco “actual control” over the Taxpayer.

SCC Decision

Justice Rowe, writing for a seven member majority, upheld the FCA’s decision, but for different reasons. The majority held that the object, spirit and purpose of subsection 111(5) is “to prevent corporations from being acquired by unrelated parties in order to deduct their unused losses against income from another business for the benefit of the new shareholders.”[6] The majority held that for purposes of the GAAR analysis, the relevant question is not whether subsection 111(5) requires a change in de jure control, de facto control, or some other form of control. Rather, the relevant question is whether the transactions frustrated or defeated the object, spirit, or purpose of the provision.

The majority held that although subsection 111(5) applies a de jure control test to determine when a taxpayer is restricted from using losses to reduce its income, that does not mean that the de jure control test encapsulates all of the circumstances Parliament intended to prevent. The text of the provision is an important factor in determining what Parliament intended, but it is not exhaustive of that intention. Through an analysis of the legislative history of subsection 111(5), the majority observed that Parliament’s intention has always been to restrict the availability of non-capital losses where the “locus of control” shifts from one person or group to another and there is a discontinuance in the corporation’s business.[7]

The majority concluded that, even in the absence of a change in de jure control, the following factors, taken together, demonstrated that the Taxpayer frustrated the object, spirit, and purpose of subsection 111(5): (i) compensation was paid for the use of tax attributes,[8] (ii) contractual rights were granted to oversee the makeup of the board of directors,[9] (iii) “veto” rights were incorporated in the Investment Agreement,[10] and (iv) the ownership of significant equity in the Taxpayer.[11]

In a strongly worded dissent, Justice Côté held that the transactions were not abusive, finding that Parliament has always intended that the acquisition of de jure control be the triggering event for whether the loss restriction rules apply. In so doing, she noted that where specific anti-avoidance provisions such as subsection 111(5) are precisely drafted and gaps are left in the legislation, it is likely that Parliament left such gaps intentionally; the reliance on such gaps by taxpayers should not be abusive. The effect of the majority’s decision, she held, was that even where a Taxpayer complies with a specific anti-avoidance provision, the Minister can nonetheless use the GAAR to effectively re-write that specific anti-avoidance provision into something broader.

Discussion

The GAAR has long been criticized for creating uncertainty for taxpayers. The majority’s decision will give fodder to this criticism.

The majority reasons serve as an important reminder that in GAAR cases, taxpayers cannot rely too heavily on the text of the relevant provisions. Legislative history and other technical aids play a significant role in determining Parliament’s intention, and may even override the clear and unambiguous words of the statute[12] or a specific anti-avoidance provisions setting out clear conditions.[13] The text of the provision is the means by which Parliament chose to convey its purpose, but it is not necessarily exhaustive of that purpose itself.[14]

The majority also clarified that the GAAR was not designed to apply exclusively to unforeseen tax planning.[15] In this respect, the majority clarifies a statement the Supreme Court made in 2021 in Canada v. Alta Energy Luxembourg S.A.R.L.[16] In that case, the majority held that the GAAR is designed to catch unforeseen tax strategies.[17] Here, the Court stated that while the GAAR may apply to unforeseen tax strategies, it can also apply where Parliament knew about the tax strategy and there is evidence that Parliament drafted a provision intended to prevent that strategy.

Indeed, the relevant consideration appears to be not simply whether Parliament knew about the tax strategy or not, but whether it was prepared to accept the strategy. In Alta Energy, the Court found that Canada knew that multinational companies would use the Canada-Luxembourg Treaty to “treaty shop”, but accepted this trade-off because it thought it would lead to more foreign investments in Canada.[18] By contrast, in Deans Knight, the extrinsic aids showed that Parliament knew about tax strategies designed to trade losses, but they did not accept them and tried to find ways to prevent them. The SCC did not consider in Deans Knight, as they did in Alta Energy, the policy trade-offs the government made in drafting the specific anti-avoidance rule in subsection 111(5), i.e., that Parliament expressly chose de jure control among other, less strict and less clear standards when drafting subsection 111(5).

In fact, a concern with loss trading was one of the reasons for enacting the GAAR back in 1988.[19] It is also worth noting that the Court’s statement that the GAAR is not designed to apply exclusively to unforeseen tax planning echoes one of Parliament’s proposed amendments to the GAAR in Budget 2023.[20]

Finally, the majority commented that tax avoidance is “largely conducted by sophisticated parties with the ability to properly evaluate the risks inherent in a GAAR reassessment”.[21] In practice, any such risk assessment will be increasingly difficult. Transactions involving the circumvention of the acquisition of control rules have been prevalent for decades. The Canada Revenue Agency has issued rulings permitting such transactions.[22] In a context where the knowledge of the government and its specific actions in choosing the relevant legal standard is not necessarily conclusive of its intent, Deans Knight will make it increasingly challenging to assess in advance whether a transaction is abusive.[23]

***

[1] 2023 SCC 16 (“Deans Knight SCC”).

[2] As provided in the Investment Agreement, this amount was guaranteed to New Forbes in exchange of the remaining shares, upon acceptance of a takeover transaction opportunity presented by Matco, whether or not this opportunityultimately materialized.

[3] Deans Knight Income Corporation v. The King, 2019 TCC 76 (“Deans Knight TCC”), aff’d Canadav.Deans Knight Income Corporation, 2021 FCA 160 (“Deans Knight FCA”).

[4] Deans Knight TCC at para 134.

[5] Deans Knight FCA at para 93 (our emphasis).

[6] Deans Knight SCC at paras 78 and 140.

[7] Deans Knight SCC at para 110.

[8] Deans Knight SCC at para 125.

[9] Deans Knight SCC at para 130.

[10] Deans Knight SCC at para 131.

[11] Deans Knight SCC at para 133.

[12] Deans Knight SCC at paras 59 and 60.

[13] Deans Knight SCC at para 71.

[14] Deans Knight SCC at para 59.

[15] Deans Knight SCC at para 45.

[16] 2021 SCC 49 (“Alta Energy”).

[17] Alta Energy at para 80.

[18] Alta Energy at para 85.

[19] Deans Knight SCC at para 43.

[20] See proposed paragraph 245(0.1)(c), which provides that “The GAAR can apply regardless of whether a tax strategy is foreseen.”

[21] Deans Knight SCC at para 49.

[22] Canada Revenue Agency, Ruling 2003-0031823.

[23] Deans Knight SCC at paras 153 and 154 (dissenting opinion of Justice Côté).

GAAR Income Tax Act Supreme Court of Canada Tax Court of Canada